Racking, Clarifying, Filtering, and Fining Your Mead

By Ulf The Viking King Of Northumbria | Making Mead

As we all very well know by now, there are so many fantastic meads out there for you to buy and try at your leisure. However, if you’re a true mead fanatic, you’ll agree that there’s nothing quite like the pleasure that comes from making your own sweet nectar.

As we’ve already seen, the mead-making process really isn’t really that complicated (although that’s not to say you’re going to get it spot-on every single time, or that practice doesn’t make perfect), and by getting stuck into making your own honey wine, you’re connecting yourself to an unbroken chain of craftsmanship which stretches back through the millennia. And that, my friends, is called: satisfaction.

This week, we’re going to be looking through the latter steps of the mead-making process, namely the racking, fining, and filtering processes in a bit more deeply, and see how best to approach these steps, and what differences they’re going to make to your eventual bottles of mead.

So, without further ado, let’s get to it….

Racking Your Mead

Once your mead has finished its primary fermentation, the must needs to be racked off the lees. This might have to happen within a couple of days after the fermentation starts, or a few weeks, or even few months – it all depends on how quickly your musts ferment, and it’s worth keeping a close eye on how much it is bubbling away to ascertain when it best to do this. What you don’t want is your mead to sit on all those waste proteins and dead yeast cells, as this can result in your mead tasting a bit iffy when you finally come to drink it.

Generally speaking, it’s best to rack your mead as soon as the primary fermentation has completed, or to wait no longer than a month to avoid any sort of spoilage.

But what is racking? Essentially, racking is the process which involves siphoning off the clear mead away from the lees, or any other lumpy bits which have formed in the liquid. In order to do this, you’ll need a siphon (a tube which allows you to move the liquid from the murky container into a new one). This isn’t a difficult process – all you really need to do is to place the full container at a higher level than the empty one, and get the siphoning going, then allow gravity to do the rest for you. Quick note – we’re sure that real Vikings did this by sucking on the tube… but fermented must isn’t something you really want to get in your mouth, and the germs from your saliva probably aren’t going to do your mead any flavors either. Get yourself an auto-siphon, and avoid any unpleasantness this way!

The first time you rack your mead, it’s pretty likely you’ll make a bit of a mess. Make sure you give yourself plenty of space, and have a few towels to hand… it’s something which does require a bit of practice, but once you’ve got your technique sorted, you’ll be able to easily avoid getting sticky mead all over your battle armor (or lino flooring). We’d always recommend finding a way to get your carboy to sit at a slight angle while you’re racking – this allows the mead to pool to one side as the level starts dropping, and ensures you have less wastage. It’s understandable that you’ll want to try and get every drop of clear mead into your new container, but don’t try and push your luck and suck up too much of the stuff near the bottom. All that will happen is the lees will end up being transferred, and you’ll have to do the whole process again!

Once you’ve successfully racked off the mead from its primary fermentation, you’ll want to repeat the process every couple of months of so. You can keep an eye on your mead and see for yourself how quickly it is clarifying (most meads will clarify nicely on their own by repeated racking and waiting), and after about six months, you can tell if it’s going to clarify (known in the industry as ‘falling bright’) all by itself. Ideally, the line between the clarified mead on top of the carboy and the murky mead below it will drop and drop, until eventually, the mead will be almost entirely clear, and any lees or other residue will just collect right at the bottom.

Time Is Your Friend

Following on from the previous point, it’s important to remember that mead making is something which really shouldn’t be rushed. The creation of mead is a slow, gradual, natural and really rather beautiful process, and one which takes its own sweet time. We all want a crystal-clear golden mead – one which catches the sunlight in the glass, and shimmers beautifully like the Nordic sun bouncing off of Arctic waters – but in order to achieve the best clarification, your best bet is to give it plenty of time, and to commit to regular racking.

We reckon that by allowing the clarification process to come about naturally, you’ll be able to make a mead which really packs in the deepest, most satisfying flavors. What’s more – just like with a fine wine – this ageing process softens away some of the harsher edges of the mead, and allows for subtler secondary flavors to come through in the glass.

Clarifying and Fining Your Mead

OK – we’ve made our point about using time and racking to clarify your mead. However, we do understand that you might not always have nine months or more to allow that to happen (those monasteries aren’t going to raid themselves, after all). Mead-making takes up a fair amount of space, and it may well be that you don’t want huge carboys blocking your way for longer than necessary, or perhaps you want to give your mead as a gift for a special occasion which is fast approaching. We get it, believe us.

If your mead isn’t clarifying properly after six to nine months, it’s likely there is a surplus of protein in your liquid, or pectins, or other substances held in the honey or water you’ve used, which have settled and are stubbornly refusing to budge. If this is the case, you’ll have to consider using a fining agent – and there are many options available. Here are some of the most accessible for you to consider:

Bentonite

An absorbent clay that bonds with all those unsightly particles bobbing about in your mead. It comes in powder form, and you have to mix it with boiling water and soak it overnight, before mixing it though your mead. Bentonite is highly effective, but it will produce a lot of lees… so you’ll need to rack your mead another couple of times after using it.

Sparkalloid

The brilliantly-named sparkalloid (is it just us that thinks it sounds like an 80’s cartoon superhero sidekick?) is a combination of seaweed and earth, which cleverly produces a positive electrical charge in your mead. This causes the particles to repel each other, and settle on the bottom of your carboy, where they can be racked off relatively easily.

Isinglass

Made from the swim bladders of the sturgeon fish (yum!), this is a fining agent which is recommended for very pale meads. Once fined with this substance, your mead may require extra tannins to be mixed in.

Pectinase

Pectinase is a pectin enzyme which is great for breaking down the suspended pectin in your mead. It can help speed up the clarification process during fermentation, so you can actually add this substance before you set about clarifying and fining your mead.

Filtering

There are more than a few disagreements on the mead scene when it comes to pretty much any aspect of mead making… and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. We like the fact that mead lovers are protective and passionate about their way of doing things, and from these disagreements, we can strengthen our own positions, or take on board what others are saying. However, when it comes to filtering mead, we really reckon that there are plenty of people out there going about things the wrong way.

The fact of the matter is, mead is a drink which is supposed to show off its natural credentials. It’s made from honey – an almost magical substance which packs in mountains of flavor and character – and filtering seems to strip away so much of the character of mead, it seems nonsensical to do it. If you’re put off by a tiny bit of residue or cloudiness in your mead, then fair enough – filter away… we’ll try not to judge you. However, we’d strongly argue that in that slight cloudiness, those little inconsistencies, there lies the genuine article and the real soul of your drink. This is the nectar of the Vikings, of Medieval kings, of ancient cultures which prospered and plundered – and believe us, they weren’t bothered about filtering their tipple, so why should you be?

Even the wine industry (with all of its pretensions and obsessive attention to detail) has started to shy away from filtration and manipulation, and there’s a growing and highly influential trend in winemaking as a whole against filtering their produce. We want to taste that natural hit of sweetness and complexity, we want that bouquet to smack us between the eyes, and we want our mead to shine like the morning sun… and frankly, it’s our opinion that filtration cuts the balls off our favorite drink, and robs it of its true expression.

Corking and Bottling Your Mead

As any mead-maker will tell you, there is no part of the whole process more satisfying and pleasing than when you’re finally pouring your mead into its bottles, and popping those corks in the top of them. It’s the summation of all that hard work, all of that waiting, and – believe us – it’s absolute thrilling to see those bottles lined up in a row, showing off the stunning colours of your beautiful new drink.

It goes without saying that before you set about corking and bottling your mead, everything needs to be whistle-clean and sterilized first. Germs spread quickly on glass, and you want to make sure your mead is as perfect as possible before you start handing it out to your mates, or enjoying it on your own in front of a roaring fire.

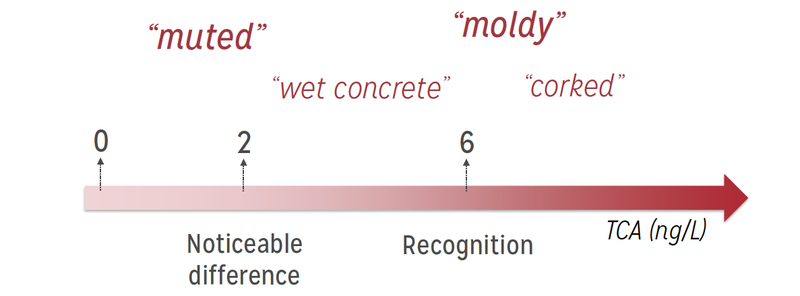

You’ll need to choose your corks and bottles wisely, too. Sure, if you want to drink your mead soon after bottling it, you haven’t got a huge amount to worry about – even a screw cap will do the job nicely. However, if you want to age your mead and explore its potential, you’re going to need something a bit more substantial – you want a cork which is going to allow in those miniscule amounts of oxygen needed, in order to create the magic that is the ageing process. It’s no good going with bog-standard cheap corks for this; you really need something of a decent quality, free from any taints, and which is going to do the job well. What’s more, you’ll want bottles which are designed for real use (rather than for decoration), as pressure changes within the bottle are going to put some strain on the glass. You can read all about how to choose your corks etc in our corking guide here.

In order to age your mead, it’s best for your bottles to be stored in a cool, dark place – sunlight will speed up with oxidation process, and can result in your mead spoiling well before its time. What’s more, exposure to heat will cause your mead to expand within the bottle, which could force the cork upwards from the neck, and allow too much oxygen inside… again, something which could be disastrous and might ruin all that hard work you put in!

For similar reasons, you’ll want to store your bottles on their sides in a wine rack or something similar. Why? Because the cork must always be in contact with the liquid, in order to ensure it stays moist and in place. Corks which dry or shrivel over time are going to lose their control of the amount of oxygen which penetrates the bottle, once again leading to too much oxidation. You don’t need access to a dungeon or specially-made wine cellar – most of us manage absolutely fine with a basement or garage!

Unbroken Traditions and Delicious Rewards

So, there you have it – a brief (ish) guide to racking, fining and filtering of your mead. It might seem like a lot to take in, but really, mead making is something which works best when it is driven by instinct, and fostered through patience and an unhurried, relaxed approach.

One other note: like most hobbies, there is plenty of healthy debate regarding the best way to go about things. Here at The Men of Mead, we’ve got a fairly clear idea of what we want our mead to be like, and prefer to stick by the traditional methods that make us feel as much like battle-weary vikings as possible… but you don’t have to take our advice as gospel.

There are plenty of variations out there open to you, so use our guide as a starting point, and then see what works for your own personal preferences. Half the fun of mead-making is coming up with your own signature style, and once you’ve got the basics mastered, the world is your honey-drenched oyster.

Cheers!